Think of all the suspense setpieces we've lost since we abandoned our faithful old landlines for these newfangled space phones in our pockets: answering machine messages echoing through empty houses, estranged spouses shouting over the recordings “I know you're there, asshole, so pick up the phone!” Busy signals, operator interrupts, calling information, calling the operator, jiggling the trunk switch before breathlessly intoning, “The lines have been cut.” Lines getting cut!

Horror novelists haven't turned out nearly enough telephone horror, but it's out there if you look hard. Besides spy thrillers like Telefon and horror novels like Phone Call there's this week's book:

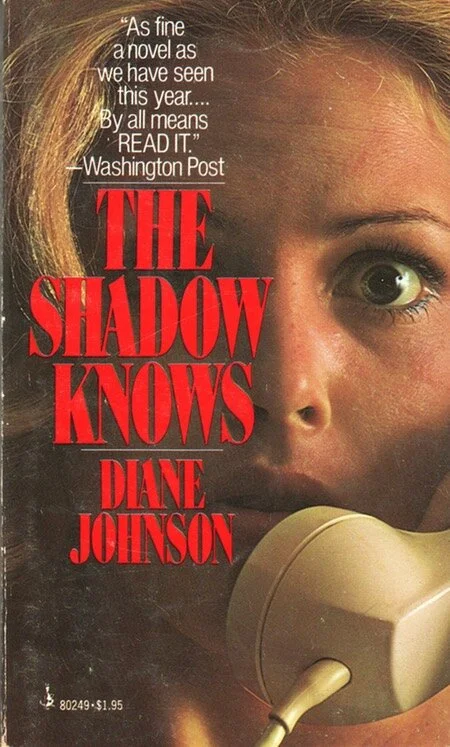

When I started reading The Shadow Knows I was blown away by the author's style, and about halfway through the book I Googled her. Turns out, I'm in good company. When Stanley Kubrick read The Shadow Knows he was so impressed he hired Diane Johnson to write The Shining. I can't do anything that fancy, but I can at least turn some of you folks onto her book. Despite having written a previous novel about a fire destroying Bel-Air, Johnson wasn't really a horror novelist before she wrote The Shadow Knows and she never wrote anything, besides the screenplay of The Shining, you could even remotely consider horror after.

But The Shadow Knows is straight-up horror, told from the point of view of a young woman (whose name we never learn, a bit like the narrator of Rebecca) living with her four small children in a crummy Sacramento housing project, barely able to make ends meet after her husband divorced her and his lawyers took her to the cleaners, using her unapologetic admission of an affair to leave her with nothing. Now she’s trying to get a graduate degree so she can find a job good enough to provide for her kids.

The story takes place over the course of the first week of January, as the narrator (sometimes called “N”) realizes that someone is stalking, and will probably kill, her. At first she's surprised that “an unknown person can suddenly be trying to kill you; you know not why, you are just you.” She can't figure out what she's done to warrant the cats on the doorstep, her front door hacked to bits with a knife, a mysterious stranger peering in windows, or her car windshield smeared with vomit.

Depressed at the relentless poverty in which she's raising her children, she says of the thin-walled, cramped apartment where they live, “When the murderer comes, people will hear our shrieks but not pay any attention, that’s how full of shrieks the place is.” And her attitude to the murder is less one of alarm and more of vague regret and befuddlement:

“It’s hard to have an attitude to murder because it hasn’t happened to you before. You tend to think what a shame, what a shame it would be to be murdered; that would spoil everything.”

But thinking back on her life, she gradually starts to realize, “Here is another thing it is important to decide: if someone is trying to kill you, do you maybe deserve it?” Eventually, the constant threat of death gives her a purpose, “…waiting to be murdered has given me you might say something to live for.”

Waiting with her to be murdered is her live-in housekeeper, Ev, a bone-thin African-American woman with a cutting sense of humor and terrible taste in men (her own brother stole her glasses, her former lover made her live in a whore house, her current lover cuts her when he's drunk).

While both women wait to die (Ev's as fatalistic as N) they don't get too fussed about the obscene phone calls that keep coming because they've been getting them for years, ones that begin, “Happy New Year, you white trash whore.” Who's calling? As N says:

“...asking myself that question, who could it be that wants to hurt you? I answered very promptly: Gavvy or Osella. I suppose if you ask anyone who it is trying to murder them, they will straightaway name loved ones without hesitation.”

Gavvy is her ex-husband, but Osella is his childhood nanny. An enormous African-American woman from Alabama, she raised Gavvy (short for Gavin) and when he and N had their first baby his parents sent Osella to take care of it, too. N is creeped out from the beginning by Osella, especially when she catches her husband sitting on Osella's lap and talking to her as if he's a child, but it's not until the day Osella has a nervous breakdown and tries to murder N that they terminate her employment. Then she starts stalking N in her spare time.

Shortly thereafter, N took up with her husband's boss at his law firm, dreaming that he'd leave his wife, Cookie, who does the typical things a wronged wife does in these kind of books — new hairdo, goes on a diet — but after stringing N along for a while, her lover decided to stay married:

“Everything that Cookie has been told will turn out to be true. How is it that some people are provided with the correct information right from the start and from others it is scrupulously kept?”

N thought it was okay to find love with someone else, and wasn't at all ashamed about her affair when she revealed it to her husband. And so, she wound up divorced for, as she put it, the sin of “thinking I could do as I pleased.”

The Shadow Knows is a frustrating book in that it never quite resolves the question of who is stalking N and why, but it trafficks in so many tense setpieces that you have to classify it as a thriller. The writing is so insanely sharp that it's impossible to dismiss and, after all, if it impressed Stanley Kubrick then it has to be good. And it's very, very funny.

In a way, I feel like The Shadow Knows fits into first-person women's humor of the Diary of a Provincial Lady mould: self-deprecating underemployed women writing about the trials and tribulations of being a mother with their tongues firmly planted in cheek. It's hard to take Johnson too seriously when she writes:

“Congratulations, marvelous organism, to have come through this week of terror and apprehensions and be sitting sturdily on a chair in your kitchen drinking beer at the end of it.”

It's a more savage Erma Bombeck who writes lines like:

“As they say: I knew what I had to do. It seemed clear to me on Tuesday morning, rising clear-eyed on an ordinary school day early in the New Year, that besides having the tires fixed and finding another baby-sitter and tracking AJ down to get Ev's car back or else the $150 she owes Mr. Probst, because I can't spare it, and finishing my seminar papers — it seemed to me that among these things, in about third place after the tires and baby-sitter, for life must go forward and events in their proper sequence, I would have to find out for myself who killed Ev.”

And that line is followed by one of the most hilarious, mortifying, and horrible scenes I've ever read as N miscarries her lover's child while shopping for tires at an automotive repair store where someone she knows is trying to help her buy just the right radials. That everything ends in a surreal fugue just makes this book more confounding and weird and frustrating. It's as if it toyed with being a horror novel for two-thirds of its length before deciding to become Blue Velvet.

Like Hugh Zachary's Blood Rush this is a book where a white author writes black characters (Ev and Osella, among several others) in a way that might make modern readers cringe, but not because it's tone deaf or traffics in dialect. Johnson has a real ear and compassion for women's voices, black or white, and Ev is one of my favorite characters — all practical and no-nonsense, while pursuing plans that are nothing but impractical nonsense — and Osella is an amazing creation who manages to be menacing, appalling, embarrassing, and ultimately triumphant. But Johnson doesn't treat them with any more reverence or respect than she treats N, and nowadays that can seem jarring.

What The Shadow Knows strongly suggests is there might have been a more interesting version of Kubrick's The Shining told from Wendy's point of view. In fact, Johnson has said as much in an article she wrote about the writing of the movie, talking about how surprised she was that Kubrick took so many of her lines away from Shelley Duvall. You can get an idea of what she had planned for Wendy by reading the 81-page treatment she and Kubrick wrote, before filming began.

Ultimately, The Shadow Knows proves two things: that Diane Johnson was capable of writing seriously strange and beautifully written thrillers, and that the next time you want to reach out and touch someone, it's safer to use the mail.

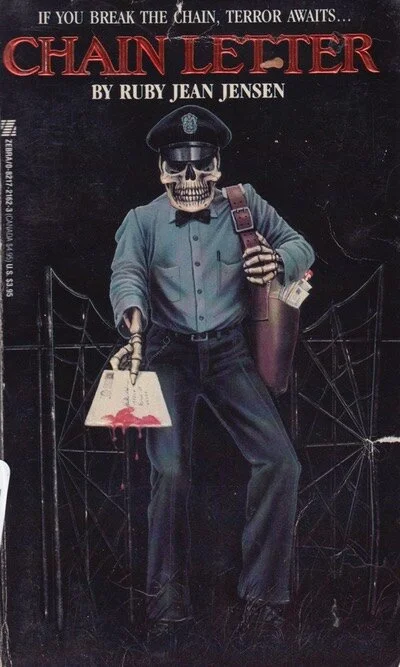

Oh, wait. Never mind.