My piece on the much-loved and wildly influential Choose Your Own Adventure book series is up on Slate, but unfortunately there wasn't enough room to include more than brief excerpts from the interviews I did with a lot of fascinating people for this story. Enter the magical world of My Website.

R.A. Montgomery (aka Ray Montgomery) was one of the two founders of the CYOA series and he wrote dozens of them for Bantam Books (the other founder being Edward Packard). In recent years, Montgomery reclaimed the rights to the Choose Your Own Adventure trademark and his old CYOA books and he's republishing them, as well as publishing new interactive books, under the Chooseco banner.

In November, 2014, he passed away. Here is the interview I did with him back in 2011.

(Well, actually, I emailed questions and then he was interviewed by Chooseco's publicist, Melissa Bounty, who took on the Herculean task of recording and then transcribing his interview, then having him expand some of his answers.)

How does a book in the series come together? As an editor, what are the guidelines the writers have to understand, and how much information do you give them for an assignment - just the title? A treatment? A more developed plot?

R.A. Montgomery: Many people have asked me how we go about creating a Choose Your Own Adventure book in the series. We have used a lot of different writers and it's a very straight-forward approach: Choose a subject, be excited about that subject, know as much as you can about that subject, and embrace that subject. Very often, I will work with an author on the subject matter, on the title, but the story really should come from the author themselves. It should be something that excites them.

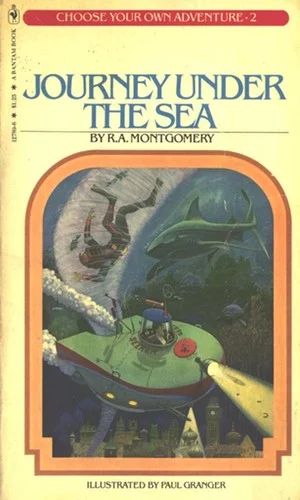

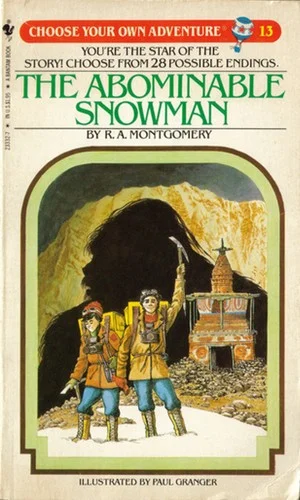

For example: Jim Wallace wrote about the Titanic, a subject that fascinated him since he was a boy. He also wrote about the mountain gorillas in Africa after he had spent time teaching in Uganda and traveling throughout Africa on his motorcycle where he visited Jane Goodall and the mountain gorillas. Jim Becket, who wrote Inca Gold and quite a few other titles for us had been a champion ski racer and spent a lot of time in Chile, spoke fluent Spanish, worked for the UN in Geneva, Switzerland, is an adventurer and a filmmaker. He wanted to write about the Incan civilization. He came up with the title Inca Gold. I myself have spent a lot of time in the mountains, mountain climbing, skiing, traveling, I've been in the Peace Corps, I've been a teacher, a writer, and a publisher. I have done a lot of the things that I write about. The Abominable Snowman, the subject of the first CYOA in the current series, is a subject that really fascinates me. Who are the yeti, that supposedly roam the high mountains of the world?

It's got to be a subject that interests the writer, or else it isn't going to be good. The most important thing is to have a writer that's interested in the subject. We don't really — and when I say "we" I mean Melissa, Shannon, and myself — we don't really give a lot of direction to the writer themselves. We found that if we do, the book comes across with less of the impulsiveness and spontaneity than it would with someone who's writing of their own interests and their own needs.

On the question of multiple endings? Multiple endings with the Choose Your Own Adventure books are really mini role-playing simulations in book form. The role-playing simulation depends upon You in second person singular, which is a format that is not unique to Choose Your Own Adventure. Second person appears in many different instances of writing and gaming, and it's very powerful because it puts you, the reader, in the driver's seat. In a simulation, it puts you, the character, in a position to make decisions and solve problems. When you put together a book with multiple endings, it all comes down to the fact that we in our lives are confronted with choices every day and we have to make those choices. It's a very natural thing to write a CYOA book:

#1. Be passionate about the subject.

#2 Know the subject well.

#3. Allow your fantasy to have free reign, or to go as far as you can go. You always have the right to change it. We believe in always having the right to fail. What does that mean? It means if it doesn't work, change it and go back and do it again.

The series has run for close to 200 titles. What are the two or three titles you feel are the strongest and make the best use of the concept? What are the two or three titles you feel didn't quite come together?

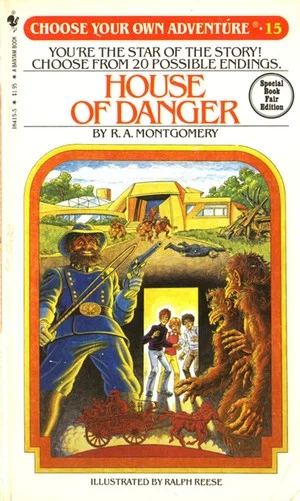

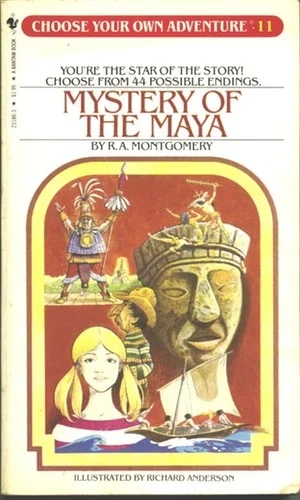

R.A. Montgomery: I can only speak for my own books. My favorites are The Abominable Snowman, Journey Under the Sea, and Mystery of the Maya. But maybe I’m not the best judge. I don’t particularly like House of Danger, don’t feel it’s very compelling, and yet it might be one of the fans’ favorites, judging from mail. The ones that didn’t work are the ones that probably didn’t interest me that much, or that I wrote when I shouldn’t have, when I was worn out from too much writing.

Has there ever been a concept for a CYOA book that was too complex, or too ambitious that had to be abandoned?

R.A. Montgomery: I've had a couple of books that just didn't work, just didn't come together. There was a book I tried inspired by a Ray Bradbury book — or maybe it was Asimov - about a journey through the body, you miniaturize yourself and take a journey through the human body. I thought wow — I'd been on the ski patrol at Mad River Glen and I'd also been on the ambulance crew, the first one in our town, and I'd done a lot of training for all of that including an EMT course. I'd always been interested in medicine to a certain extent, so I thought what a wonderful journey, what branches you could take through the heart and the liver and the brain and the pancreas and the bones and the blood system — but it was a total failure! I couldn't do it. I had a miniaturized you going through the body and I had white blood cells and red blood cells and platelets and oxygen transfers and I couldn't do it. I gave it up. I knew it was not turning out well it was not going to be a good book. Other writers I'm sure have had similar issues, where they started a title and it just didn't work out so they came up with something new. When a title doesn't work, it's quite obvious.

[Note: The book he's talking about is FANTASTIC VOYAGE, based on a story by Otto Klement and Jerome Bixby. Isaac Asimov wrote the novelization of the movie.]

What do you consider the key attribute of making a CYOA book work? What is that element that makes them really come alive?

R.A. Montgomery: As I said earlier, a writer has to have passion about their subject if it's going to come alive, and they have to have knowledge about that subject. And I think you can make any kind of subject a book — you can explore the world of ants, you can explore the world of space travel, you can explore the world of an outlived civilization that collapses, imaginary or real. You can journey under the sea and explore the creatures that live at 35,000 feet below sea level. You don't think anyone lives down there, but they do! And you write about it.

Then comes this element that many of our writers understood and some didn't, and the ones that didn't, we didn't end up publishing. What is it? It's compelling choices. It can't just be: turn to the right or turn to the left. That gets boring pretty soon. And sometimes those choices are needed to make the plot advance, but it's got to be a compelling choice. And what is a compelling choice? A compelling choice is a choice that gives you some context about the risks involved.

Do you decide to go into the ice fall at the foot of Mount Everest, despite the fact that it's eleven o'clock in the morning, and the sun is high, and it's melting the seraks, these giant ice needles, but you need to look for your lost friend These ice needles start to become melted at their base, these 20, 30, 40 foot high ice needles. They can crash, and this part of the glacier, the terminal moraine, is a death zone. It's a killing zone. And on Everest this is where a lot of people do die, when the ice cracks and falls. So, you can choose to go in right away, or wait for another day, or wait for a helicopter rescue crew that might or might not get there. That's a compelling choice. It's not: gee, you came to a fork in the road and one goes left and one goes right, well, what do you do? That’s a choice, but it's not compelling, it’s random.

Do you think that the endings should be related to the choices? Should a choice that's harmonious to the universe, does it always net a good ending for the reader?

R.A. Montgomery: A lot of people ask, and have asked over the years, is there a moral imperative behind the choices that are presented in Choose Your Own Adventure and the answer is: actually, no. Life throws you many curves. The choice you make might very well have a moral tone to it. Should you go in and save your friend in the ice fall now, or should you wait? Waiting may very well end up in his death, so if you choose to rush ahead, that’s a choice based on “good morals,” but in CYOA this doesn’t necessarily net a successful ending. This is accurate to the decisions you make in life.

Choose Your Own Adventure, in its complexity, does not give you a clear cut path to a correct ending. Over time, we developed permutations on the number of storylines. In the early books there were 120 pages to as many as 30 or 40 different endings — there were anywhere from 150 to 200 separate storylines that emerged. There's no way we could have programmed a moral ending for every storyline, unless every ending was happy-go-lucky and moral. Life isn't that way. Choose Your Own Adventure is not that way. Choose Your Own Adventure is a simulation that approximates, the choices that we face in our lives. If life were mostly really exciting and taking place in a dugout canoe or mountaintop or castle dungeon most of the time.

The CYOA books are famous for featuring a non-gendered protagonist in the text, and for often not having an ethnic identity assigned to the protagonist. Was this a conscious choice, or just a side effect of writing in the second person?

R.A. Montgomery: From the outset, we wanted Choose Your Own Adventure books to be non-gender specific. We wanted girls and boys both to feel fully involved in the storyline, so that was a conscious decision and one that we support to this day. The storylines are intended to empower people by telling them that they are world-class mountaineers, or young doctors in the Amazon, that they are archaeologists, that they are newspaper reporters, that they are pilots of small airplanes, a variety of truly exciting professions which, because there is no gender, is saying to girls: you can be anything you want. And it says to boys: you can be anything you want, too. And that is something that we believe that Choose Your Own Adventure does support, all along the way.

As far as the artwork goes, if you know something about film, you know about the approach called subjective camera, in which the film is depicted through the eyes of the hero of the film, without you ever seeing the hero of the film. That's essentially what we do with our illustrations — we direct the artist to always have a subjective camera kind of approach, through the eyes of the you, looking at the scene. Occasionally, we will have a shoulder, a head, the back of the head, or fingers pointing, but we rarely depict a full facial view, or if we do it is not gender-specific. It could be interpreted either way.

Isn't this something Chooseco has been able to do and control, while in the original publications Bantam did use gendered illustrations?

R.A. Montgomery: Sometimes they did. We always gave pushback. And it was hard for many illustrators who were used to seeing everything including the characters in a scene.

How did you construct the actual, physical map of the text? Figuring out which pages led to which choices, where to locate the endings, etc? Was that a difficult process?

R.A. Montgomery: Different writers work with the map in different ways. I sketch a map out and try to make the story match the map as I write. I don’t seem to have a problem with this. Other writers draw the map as they plot along. The story dictates the map, not the other way around. If you’re trying to learn how to do it, it’s interesting to plot a map from a couple of different books to see how differently they can turn out.

Did CYOA get a lot of fan mail? Did you have an idea of what the average reader was like?

R. A. Montgomery: In the early years of CYOA, we literally got thousands of pieces of fan mail. I finally had a postcard printed up with a picture of me hiking and climbing in the Himalayan mountains, and we would send that back to the child or the adult who wrote in. Today, we get a lot of email messages from people. We still get letters from kids, but we also get email messages literally from all over the world. And I was recently in Vietnam, in Saigon, and up in Hanoi, and I was also in Thailand — we travel a lot, that's where many of our ideas come from — and I met people from Vietnam, from Cambodia, from Malaysia and from Thailand, who all knew Choose Your Own Adventure from their childhoods. So we have fans all over the world. Don't forget, we were in 28 — well, I think 28 is low — we were probably in 30 to 35 or more foreign languages. Interview: So no "average reader" then, pretty difficult to distill it down to a certain person.

Many fans have noticed that while some of the early books in the series were very open-ended, later installments became more linear and more story-like with definite endings and less alternate endings. Was this a conscious choice? A response to reader requests? A shift in interest on the part of the writers?

R.A. Montgomery: In the early days of CYOA, we — when I say we, I mean myself and the other writers — had quite a few more endings than later on in the series. We had as many as 30-40 endings in the first 10-15 titles. We were burning up storylines like crazy with all of those different endings. And it was fun, but if it only took 6, 7 pages to get to an ending, there wasn't a lot of room for character development, or plot development, or all the kinds of descriptive phrases that you need to build a scene.

So, I can only speak for myself, but from my point of view, as the series matured I decided to have fewer endings and more pages to get to those endings — more pages between choices — so that I could develop a plot, develop a character, and develop the setting. Was that successful? I don't know. I think that many people preferred the approach of many more endings and short, punchy ways to get to them. But there were also people that found that more storyline, more character development was fascinating to them.

Parenthetically, I think that the later books with fewer endings actually helped kids make the transition from Choose Your Own Adventure books to regular, full-length books with third person narratives and no choices.

How did librarians respond to the CYOA series? Did they resist them? Not consider them "real" books initially? Did the company have to woo them somewhat?

R.A. Montgomery: There was a bit of pushback in the very early days. But in general librarians were overwhelmingly positive and accepted Choose Your Own Adventure, from the start, both public librarians and public school librarians. Why? you might ask, because this wasn't traditional literature. The New York Times Book Review recently said Choose Your Own Adventure was a literary movement. Indeed it was. And the librarians liked it, because the kids came in and were reading. The most important thing is to get people reading, it's not the format. It's not even the writing. It's the reading. And the reading happened because kids were put in the driver's seat. They were the mountain climber, they were the doctor, they were the deep sea explorer. They made choices, and so they read. And there's nothing that pleases a librarian or a teacher more than seeing kids excited about reading.

Were you yourself, or any of the writers, interested in early computer games and did gaming have an influence on the series and its development?

R.A. Montgomery: My career after leaving college was focused on teaching, first at the high school level, then at Columbia University. I eventually started my own school, a summer school for academic remedial learning. All along, I remembered my experiences as a camp counselor at a camp up in Maine on an island, where we were taking mountain trips, canoe trips, hiking trips, all summer long. We were out of the camp more than we were in it.

What I observed then is that experiential learning is the most powerful way for kids, or for anyone, to learn something. It's not lecturing, it's experiential, hands-on learning. To a great extent, that's gaming, that's game theory. I got very interested in experiential learning, and I got very interested in game theory. When I was running a small summer school for kids that had trouble with academics, both with math and with writing and reading, we employed a lot of games and game theory approaches to learning. It was very exciting to see the result of that. They were very impressive.

Later, I worked for a high-powered consulting firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Apt Associates, which was started by Clark Apt, a professor at MIT. He pioneered role-playing simulation games, where there is a role designed for You, and there would be in these games 20, 30, 40 different people, and therefore different roles, and the objective was spelled out but not how to get there. So you had a role as to who you were, and you had an objective for the game, and then you had time-phase, task-oriented, 15 or 20-minute sessions where you came together and simulated the real world.

Can you give an example of one of the scenarios you worked on?

R.A. Montgomery: A scenario I was involved in was called In Country, and I wrote it, and was about the problem that the US Peace Corps had when dealing with volunteers. The reason was this: the volunteers were guests in a host country. Maybe they were in an ag program, or a health program, or an engineering program to build roads or drain swamps, or a teaching program in the schools, whatever it happened to be. They were guests in country. The staff were volunteers, and they were usually from industry. The pyramid was reversed, the executives of a profit-making organization are served by everyone underneath them. But in the Peace Corps, the executives are serving the needs of the volunteers and its a reversal of that pyramid.

So here came the big issue: during the Vietnam War, people in the Peace Corps were told they could not demonstrate in the host country. They could express their views in private conversation, you can't stop that, but no placards, demonstrations, marches on the capitol, etc. And a lot of the volunteers did want to demonstrate and be known, and the staff didn't know how to handle it. So we simulated and wrote a scenario for a hypothetical country and created roles for twenty different volunteers and ran through all of the contingencies of the political and the sociopolitical problems confronting volunteers, some of whom are radical, some of whom are nonradical, some of whom are right in the middle, and staff members who are very, very prone to kick people out, or very liberal, and everything in between, and we had exogenous events, because that's real life too.

So that was a model of reality that was used to run people through the types of events that they might experience when they were in country, and it was very useful. Probably the most useful thing was the post-game discussion, after a day of playing these roles, what you got out of it. The ending was unimportant: it was how you got there, and what you felt. So, that's what CYOA grew out of for me.

What was the company's reaction when so many other CYOA-styled books started appearing on the market? Did you have any recourse? And how did you change the series to take on this sudden burst of competition?

R.A. Montgomery: A lot of the competing series were published by our own publisher, Bantam! They knew a good thing when they saw it I guess. I don’t remember any particular response to it. We did some special editions that were longer, we did some short sub-series that zeroed in on a subject. But this was pretty normal publishing practice for a big series too. It wasn’t necessarily in response to competition. We were competing with ourselves at that point.

What do you think the CYOA books offer a reader today, that computer games don't?

R.A. Montgomery: It’s a more intimate experience I think in some ways. And without the constant visual feed of a video game, it leaves more to a reader’s imagination.