If you read books in the early 80's, chances are you knew the name Edward Packard. The originator of the Choose Your Own Adventures concept and the author of many of the best-loved books in the series, he is inextricably linked with that particular pop culture moment. My story about the Choose Your Own Adventure series is up on Slate, and Edward Packard was kind enough to do a phone interview that I wanted to post it in its entirety, because this is the man who was at ground zero in the move to interactive storytelling.

These days, Packard has reclaimed the rights to the books he wrote for Bantam under the Choose Your Own Adventure banner, but the CYOA brand name has been retained by R.A. Montgomery, the other major author in the series and, with Packard, one of its two founders. Packard is re-publishing enhanced versions of his books as ebooks in the iTunes store under the brand name U-Ventures. (Packard also has a personal website)

Were you aware of computer games at the time you were starting to write the Choose Your Own Adventure books? Were you a gamer?

Edward Packard: No, I wasn't. I actually thought this up in 1969 when I had some little kids and was reading them bedtimes stories and things. At that point there weren't any computers, the PC hadn't even occurred. I didn't know of any examples of this kind of interactive fiction at all. By the time the books came out things were percolating. I was never very au courant on computer games. I got my first primitive Apple computer in 1982. I do have this vague recollection of seeing Pong and Pac-Man. Around the time of Choose Your Own Adventure I did become familiar with TSR and Dungeons and Dragons because I had a kid about 12-years-old, my son, who got to be a very big D&D fan. So I definitely became aware of that. I have to say that although that was quite a different thrust I was very impressed. My son was sort of dyslexic and I was amazed at how complex the text was and the vocabulary in D&D.

What did you do before you wrote the books?

Edward Packard: I was a lawyer. I practiced law for 20 years but never felt absorbed by it. I was a counsel for RCA Records for a while; then I set up my own practice. My uncle was a law professor and my brother was a lawyer, and so I drifted into it. I'd written a couple of children's stories that I hadn't been able to sell, and I couldn't sell my first book, Sugarcane Island, either. It went in the desk drawer, and it was kind of a fluke, as so much of life is: I was in Vermont some years later and saw an article in a magazine, Vermont Life, about a small press looking for innovative children's stories and literature, and so found my first publisher.

My intent was to try to make Choose Your Own Adventures like life as much as possible with regard to the consequences of your choices. In life, usually, if you make a wise decision you do better than if you make a dumb decision. I didn't want it to be a lottery but I didn't want it to be didactic either, so that if you always did the right and smart thing you always succeed. I tried to balance it that way.

Were you aware of the tension between narrative and interactivity and how the interactivity of the series declined as it went along?

Edward Packard: I wasn't conscious of it, but it did happen. My favorite fan letter was critical of us. It said nice things about my books, but it complained that we didn't have as many endings as when we started out. My first book had 40 endings, later books averaged maybe half as many. I didn't intend to become more linear, but writing along over the years — I think it just happened. You see, there's a trade off: If you have a lot of endings you have short plots and rapid resolutions. If you want to develop the plot and characters and have twists and have more of a real story, then you drift toward having less space for endings. I think trending toward fewer endings was a natural thing that happened with the writing — not wanting to cut off the scenes and the story and, instead, letting the writing take the story wherever it might lead.

What book was it where you felt like you finally got a real grip on the possibilities of the form?

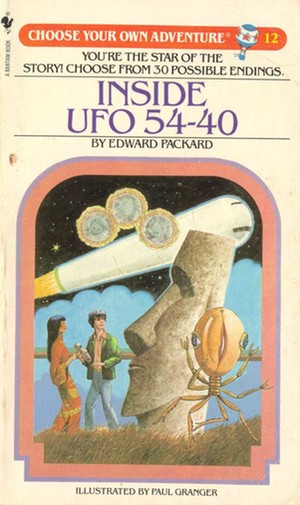

Edward Packard: I did experiment in trying to push the form further than just the standard format. Even in my first book I had a sequence where time went around in circles, going from one page back to the other, and it would keep swinging back to the same situation. In another book, Inside UFO 54-40, you learn about a wonderful planet called Ultima. The only way to get there was not to follow Bantam’s standard warning page, which was inserted at the beginning of every book, saying, "Do not read this book straight through." I altered the warning page for Inside UFO 54-40 to read, "Sometimes, for the most wonderful places, there can be no way to get there," which gave a hint at what was going to happen, and it turned out that there was no choice leading to the planet Ultima. It was just a page all by itself. You had to cheat, in effect, to get there. In Hyperspace I somehow had myself appear in the book as a character.

Do you think the format has gone as far as it can go? Is there anything left for this kind of interactive fiction beyond nostalgia?

Edward Packard: I think as far as printed books go, probably yes, but not in electronic ones. A couple of years ago I made a deal with Simon & Schuster to bring out some of my books as iPhone and iPod apps. They hired a developer and we now have two apps in the iTunes store. Because I lost access to the trademark, they’re under a new trademark –– U-Ventures.

What was the relationship between Bantam and you and Ray and how did you lose access to the trademark?

Edward Packard: Bantam had a policy of giving equal contracts to Ray and me, and we each hired subcontractors to work under our respective halves of the deal. The publisher called them R.A. Montgomery books and Edward Packard books. I kept the copyright on writers I hired, and I think Ray did the same. It was work-for-hire, but I gave my writers a share of the royalty. Ray was much more alert than I was after Random House abandoned the trademark, which I think was a serious lapse on their part. It became available, and Ray applied to register it. He formed a company called Chooseco, and has been releasing some of his books under the Choose Your Own Adventures banner. When Simon & Schuster wanted me to do books as apps I was obliged to develop a new trademark. So these apps are called U-Ventures. Ray has released a couple of his books as apps, but I believe they are reprints of the original books. When Justin Chanda, my publisher at Simon & Schuster, signed me up, he said that we should take advantage of the electronic medium and introduce features that wouldn’t be possible in the printed books, and that’s what we’ve done.

For example, in the apps the computer can remember where the reader has been and what he or she has experienced in the story, and how the story proceeds will be affected by that. You might be given a secret code that will get you to a particular page. You have to remember it and type it in correctly. You can have fast-paced action, where you must make frequent choices in a crisis situation. In this situation in a printed book, you’d have a few lines on one page and a choice, and then you have to have the rest of the page blank. This could go on for maybe thirty pages. You’d waste too much paper, have too many pages in the printed book. With an app, it’s not a problem. We made a miscalculation in programming the first U-Ventures app, Return to the Cave of Time. I thought it would be better to have the experience of going through the whole book and having to start over at the beginning of the story or at bookmarked page if you come to a premature end — I didn’t want it to be too easy to “change history,” so to speak. But some people complained that the app was too short. They didn't understand that they could make other choices and follow through to other endings. With the second app, Through the Black Hole, we allow readers to backswipe to previous choices. It’s a more user-friendly set up. We plan to revise the first app to have that feature as well.

How did you map out the Choose Your Own Adventure books when you were writing them? I imagine outlining is very different from outlining a regular, non-interactive book.

Edward Packard: At first, I thought I could keep everything in my head, but I soon got confused, so I had to work out a system, and the system is pretty simple. I make a decision tree lying on its side. A horizontal line represents the opening pages. I would then write a word or a phrase over the line; then I'd draw two branches, one above the other, and write what the choices would be for each. Above the first line I'd write, for example, "Climb up the rocky hill," and above the second line, "Walk along the beach."

I would label the second page "A," and the third page “B.” The reason to use letters instead of numbers is so you can number the pages: A-1, A-2, A-3 and so on. Then, if you expand a section you can add the numbers without having to change the numbers of all the other pages. It took me a while to work this out, because at first I used page numbers but then I found I'd have to change the numbers all the time if I cut or added something. So, when I'd start a new page I'd mark it on flowchart. And when I got to an ending, I'd just put a fat dot at the end of the line. Sometimes one plot line would flow into another and at the end of that line, in a circle, I’d put a letter for the page the track segues to.

Back to the other writers who worked under you. How did that arrangement work? How did you assign books? Did you just give them a title? An outline? Did they suggest topics and plots? It varied. When I had somebody who was a regular writer for me I might suggest an idea to them or they might suggest an idea to me. I'd say, "How about something about an alien planet?" or, "How about something where you're kidnapped?" In a couple of cases I had a really good idea for a plot, but I didn't have time to write it myself, so I'd outline it and get another writer started.

Did you and Ray Montgomery coordinate titles with each other to make sure that you weren't working on books that were too similar?

Edward Packard: Ray and I were in frequent contact in the 1980's, until near the end of the series, but we didn't consult each other on what to write about. Each of us would deal individually with Bantam. We wrote one book jointly, but that was exceptional. I don't recall any other time when we talked about it, except when I showed him how I outlined this kind of book back when he wrote his first one.

Halfway through the series it changed from adventure plots to titles that took advantage of the second person POV such as You Are a Shark. There were also a large number of martial arts books in the series. How did that come about?

Edward Packard: We wrote so many books that we began to explore more specialized subject areas and then follow up on them. One area was martial arts. One of my writers wrote about five in this genre. I wrote several sports books, about which I knew little until I read books on coaching them. I watched games on television. I wrote a book called Soccer Star though I had never played soccer. I read a book on coaching it, and my daughter, who played college soccer, gave me tips. In You Are a Shark, you turn into a succession of different animals and experience life from their point of view, a broadening experience.

The series is distinguished by the second person You point-of-view that was non-gendered. Was this intentional on your part?

Edward Packard: When I wrote Sugarcane Island, I had two daughters and one son, and he was too young to take in stories, so I started out with girls. When I'd say, "What would you do?" I was looking at a girl as the prototype reader of the book. I knew that more than half the market was girls, so I wanted to have my books appeal to them. When Sugarcane Island was published, and we were lining up an artist, Ray and I both felt that we should try to make "you," the reader, a unisex person. That didn’t work out to be wholly satisfactory, and Bantam insisted that “you” the reader be illustrated as boy because their research showed that girls would identify with boys, but boys wouldn’t read a book where "You" was a girl.

This caused a problem because most of the covers were of boys and most of the illustrations were of boys and only later on Bantam began to illustrate “you the reader” as a girl. A few years into our series, a very popular series emerged called The Babysitters Club. I think we lost a great number of girls to The Babysitters Club. Bantam started putting girls on the covers more often. In the text I was always extremely rigorous never to have anyone refer to the reader as "He." For my U-Ventures apps we decided that all illustrations should be from the reader's point-of-view, so everything that's drawn, except for occasional establishing shots, is what "you" see during the course of the story. I think it works very well.

When did you feel that the series had reached its peak? I knew that, as is the case with all series, sales trends form a curve. It shoots up and then trails off. I could see the peak being reached and sales going off. Part of the reason for the decline was competition from imitative series, although none of them were very successful. A bigger factor was The Babysitters Club, and then R. L. Stine with his series of scary books, which were tremendously successful. That, plus the rise of computer games and video games which made the interactivity of our books not such a unique phenomenon.

Looking back, what are you proud of?

Edward Packard: What I’m most pleased with is that my interactive books have generally been a force for good, for increasing literacy and love of reading among children. I think it was in the same month that I got a letter from a teacher saying, "I teach gifted children and they're so responsive to your books, they love them,” and a letter from another teacher saying, "I teach children who are challenged with reading and they love these books." That was a great to know. I’m not constructed as a do-gooder type person, but I feel really good that, inadvertently, that’s how I ended up.